The Power of Play

More and more research confirms that play is the best way for children to learn and communicate. Through play, children figure out how to interact with one another, problem solve, make decisions, collaborate, and work together as a team.

As a therapist, I have also seen the power of play first hand. When I was first starting out as a therapist, I wanted to work with elementary-school-aged kids, and I was excited to start my internship with that age group. When I met with those younger clients during those first few weeks, things didn’t go as I expected - the kids didn’t say much of anything and it didn’t seem like I was going to get anywhere fast. I went to my supervisor, perplexed about what was going wrong. He said, “You need to get down on the floor and play with them.”

When you play a game with a child, it makes it much easier for them to get comfortable and open up to you about what’s going on for them. Once I started playing, my young clients started to open up and talk about what was happening. By using play as our method of communicating, I was able to understand what was happening for them, and speak with them about trying different, healthier strategies to help manage their challenges.

The same can be said for child-to-child communication. When a child struggles socially, it can be so difficult for them to communicate feelings or frustrations to other children. Helping a child to choose a successful activity during a playdate, or having a positive interaction at the playground can make all the difference in helping them connect and bond with a friend.

Throughout my career, the power of play has presented itself again and again as a crucial component of successful interactions with (and between) children. Whether I’m working with children in schools, small groups, after school programs, or in private practice, I continue to use structured and unstructured play-based activities. It’s incredible how much children can learn and communicate through play!

What is play?

When you think of play what comes to mind? Play is different for everyone. For some people, creating art is play. For others, it’s climbing rocks. For others still, it’s writing. There are many different ways to play; it’s not just blocks and LEGOs.

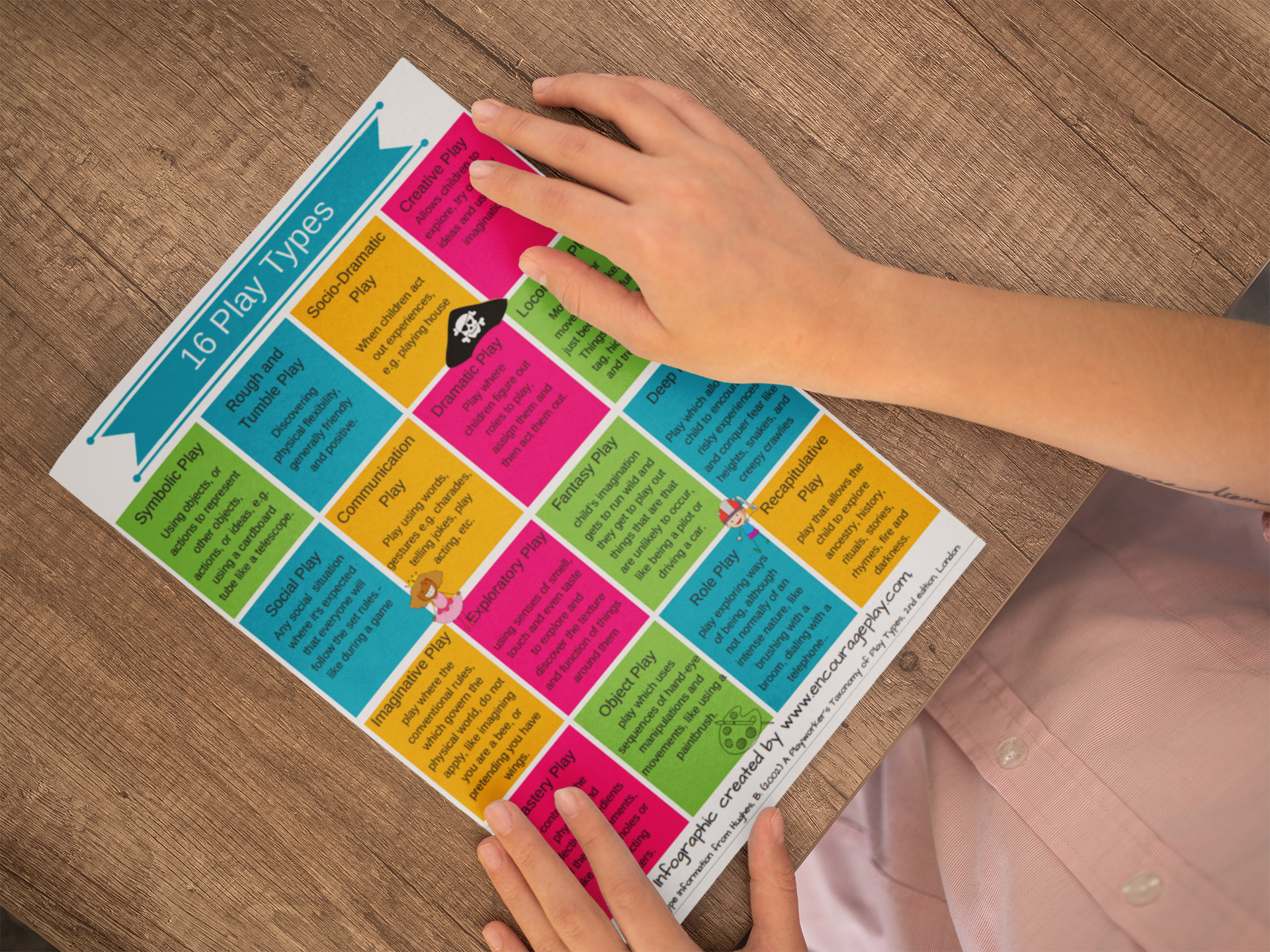

Bob Hughes has done some great work about 16 different play types that he’s identified. Take a look at what he’s found.

One playtime can encompass multiple types of play. Playing pirates can include rough and tumble play, symbolic play, dramatic play, communication play, social play, fantasy play and imaginative play!

Stuart Brown has identified 8 play "personalities". As I read these various types, I was able to see myself and my own family in these play personalities! Also, you’re not limited to only having one.

Why Play Matters

Play can and should be part of our everyday lives. Play is fun, relaxing and enjoyable but it’s also important. Play is so important that it’s even part of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1996). Article 31 states that children have the right “to engage in play and recreational activities.”

Humans are biologically wired to play. Play serves as a way for people to practice skills they will need in the future. According to The Importance of Play in Promoting Healthy Child Development and Maintaining Strong Parent-Child Bonds (2007), free play allows children to practice decision-making skills, learn to work in groups, share, resolve conflicts and advocate for themselves. It also allows them to discover what they enjoy at their own pace.

Play is a child’s natural language. It’s how they communicate their thoughts and feelings about what’s going on in their world. Children learn about self-regulation and managing their feelings through play. Through play, children also learn how to interact with others, and understand the impact their behavior may have on other people, and how other people impact them, developing their empathy and understanding.

Play is not just fun, it’s also essential. Dr. Stuart Brown (2010) talks about a lack of play being similar to a lack of sleep. Just as all humans need to sleep, they also need time to play. Free play “is critical for becoming socially adept, coping with stress and building cognitive skills such as problem solving” (Wenner, 2009).

Play can help children reset and re-energize. Children can focus more after a brain and body break. Through play, children practice and learn essential skills for life. In the book Purposeful Play (2016), three elementary school teachers talk about the power play has in preparing children for the future: “Play gives children exactly what they need now, which will help them develop into the kinds of people who can handle what comes next.”

Why Kids Struggle with Play

As individuals, we all develop at different times. When it comes to play, it’s no different. There are children who play easily with others naturally, and there are those who need explicit directions to learn those skills. Children develop different skills at different times and that is a normal and expected part of child development.

When your child is having difficulty with play, it doesn’t mean that they have an undiagnosed disorder, that there is something wrong, or that you did something wrong. We all develop at different paces over time. We can support our children by encouraging play, and supporting them and directing them when they need it.

If you are concerned about delays you are seeing in your child related to play, social interaction, speech, sensory, movement, or other milestones, I would encourage you to start first by speaking with your pediatrician to get their opinion on what you are seeing. They can then advise you if you need to take any follow up steps, make appointments with a more specialized medical professional, or let you know if they think additional evaluations makes sense.

For those of you who already have a child who has been diagnosed with Autism, ADHD, a developmental delay, etc., they may struggle with play and interacting with others. I want you to know that play matters and makes a difference for all children. Play is a powerful way to teach any child skills. It may not be linear or smooth, and that’s OK. In fact, play can help those children who need additional support and scaffolding by allowing children to practice and review these skills in a more enjoyable playful manner.

How Does Play Impact Social Skills?

Play is how children learn, including learning social skills. Learning how to interact with others, compromise, and work together all happen when playing.

As children develop and grow, so does their way of playing. Let’s take a brief look at how play develops and changes over time for children. Mildred Parten outlined the six stages of social play and it starts at birth (An analysis of social participation, leadership, and other factors in preschool play groups, 1933).

1. Unoccupied play

Did you know play starts at birth? Infants engage in random movements with seemingly no apparent purpose, but this is the beginning of play.

2. Solitary play

This is when children start to play on their own. Solitary play begins in infancy and is common in toddlers. However, all age groups can (and should!) have some time for independent play. When engaged in solitary play, children do not seem to notice other kids sitting or playing nearby during this type of play.

3. Onlooker play

The next stage of play is when children watch others play. Onlooker play happens most frequently during the toddler years but can occur at any age. The onlooker may ask questions of other children, but there is no effort to join the play. This may happen when a child is shy, or unsure of the rules, or is hesitant to join the game.

4. Parallel play

Parallel play starts when children begin to play side-by-side with other children without any interaction. Parallel play is usually found with toddlers, although it happens in any age group.

Even though it seems like they are not interacting, they are paying attention to each other. This is the beginning of wanting to be with other children their age. This stage lays the groundwork for the later stages of play.

5. Associative play

At some point, a child will start interacting more with the other child they are playing with; this is the next stage of play called associative play. At around three to four years of age, they become more interested in other children than the toys. They start asking questions and talking about the toys and what they are making. This is the beginning of really understanding how to get along with others. During associative play, children within the group have similar goals (for example: building a creation out of blocks). However, they do not set rules and there is no formal organization.

6. Social play

Children will begin to socialize starting around three or four. They begin to share ideas and toys and follow established rules and guidelines. They play shop and figure out who will play what role. They can work together to build something or maybe play a simple game together. This is really where a child learns and practices social skills, like cooperating, being flexible, taking turns, and solving problems.

“play seems to dynamically stabilize body and social development in kids as well as sustain these qualities in adults.

— (Brown, S., & Vaughan, C., 2009)

What You’ll Find Here

At Encourage Play, there are lots of resources to encourage play and build social skills, and I keep adding more as time goes on. You can search for activities by types of play or by social skills. I have activities for professionals working with kids who need support with their social skills as well as ideas for families to help practice and scaffold these skills on playdates or at home. Take a peek around!

Resources

Brown, S. L., & Vaughan, C. C. (2010). Play: How it shapes the brain, opens the imagination, and invigorates the soul. New York: Avery.

Elkind, D. (2018). The power of play: Learning what comes naturally. Vancouver, B.C.: Langara College.

Ginsburg, K. R. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bond, Journal of American Academy of Pediatrics, 119 (1), 183-185.

Hughes, B. (2002) A Playworker’s Taxonomy of Play Types, 2nd edition, London: PlayLink.

Lavoie, R. D., Levine, M. D., Reiner, R., & Reiner, M. (2006). Its so much work to be your friend: Helping the child with learning disabilities find social success. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Mraz, K., Porcelli, A., & Tyler, C. (2016). Purposeful play: A teachers guide to igniting deep and joyful learning across the day. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Nicholson, S. (1971). How not to cheat children: The theory of loose parts. Landscape Architecture, 62, 30–35.

Parten, M. B. (1933). Social play among preschool children. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 28(2), 136-147. doi:10.1037/h0073939

Reading, R. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent–child bonds. Child: Care, Health and Development, 33(6), 807-808. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00799_8.x

Singer, D. G., Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2010). Play = learning: How play motivates and enhances childrens cognitive and social-emotional growth. New York: Oxford University Press.

U.S.Cong. (1996). The rights of the child [Cong.]. Geneva, Switzerland: Centre for Human Rights, United Nations.

Wenner, M. (2009). The Serious Need for Play. Scientific American Mind, 20(1), 22-29. doi:10.1038/scientificamericanmind0209-22